Judy Lightstone, Founder & Director Auckland PSI Institute, has been providing training, and supervision for mental health clinicians for the past 38 years. She has a PhD. with a specialism in Trauma Psychology and two Masters degrees in Counselling and in Marriage and Family Therapy. She was trained in Feminist Relational Therapy for Eating Problems with Susie Orbach (author of Fat is a Feminist Issue).

Friday, May 11, 2012

Learning to Comfort and Self-Soothe

In human infants and children, the ability to comfort oneself is learned through extensive experiences of healthy "bonding" with one's caregiver/s from early on. Healthy bonding requires long periods of holding, cuddling, mutual gazing and adoration between child and caregiver/s, and that the child is kept safe and protected from abusive or violent experiences, especially in the family. Early emotional neglect, childhood abuse and/or the unavailability of reliable soothing in early childhood, which can be due to many causes, such as illness in the caregivers, can have dire consequences when the child grows into adulthood.

We now know that such safety and bonding are necessary for the infant's optimal brain development, which results in the child's ultimate ability to learn how to comfort him/herself. A child that grows up unsafe, and/or without this "bonding and holding" will be vulnerable to experiencing repeated unnecessary alerts set off by the "survival" (hind) brain throughout their lifespan; signals that survival is threatened even when it isn't. These signals shut down optimal functioning of the "human" (thinking) brain, leading to difficulties in word retrieval, interpersonal skills, and concentration when such skills may be most needed. When an adult can't naturally self-soothe, s/he may become dependent on tension-reducing activities that can appear self-destructive, but in actuality are desperate attempts to calm the body down, some by forcing a flood of endorphins. Such tension-reducing activities include smoking, drinking, self-harm, compulsive gambling, overeating, purging, self-starvation, and sexually risky behaviour. Compare this to people who grow up safe with loving and supportive caregivers, who are able to self-soothe with little effort as adults because the learning is deeply embodied from infancy.

The combination of repeatedly experiencing anxiety in situations that aren't actually dangerous, with a compromised ability to calm oneself when such anxiety does occur, also makes it more difficult to fall asleep at night or to get a full regenerative experience from sleep. Having difficulty soothing oneself can also mean having difficulty taking in comfort from others, even those who are trying to be kind and supportive. This can cause problems in one's most intimate relationships.

All of these difficulties fall under the psychological category of "poor affect regulation," which understandably often results in a tendency toward the kind of harmful attempts at tension reduction described above. Standard forms of “talk therapy” that do not address the physiological shutdown caused by an overactive survival response are unlikely to be effective, because the client will spend a lot of time feeling unsafe. When feeling unsafe, the talking (‘human”) brain is not working adequately enough to integrate verbal interventions. Therapeutic approaches that focus on analysing one's thought patterns are called “top down” therapy – because they address the “higher” brain functions while ignoring the lower brain functions, such as survival reactions.

There are a number of psychotherapeutic approaches that work from the “bottom up.” These are especially effective for those suffering from the effects of "poor affect regulation." Many of the techniques have been integrated into PSI (PsychoSomatic Integration) Therapy, and are taught to counsellors, psychotherapists and psychologists to help them learn to address these kinds of problems more effectively with their clients.

Click here to find out about distance learning programmes and here to find out about general training and supervision options.

Sunday, April 15, 2012

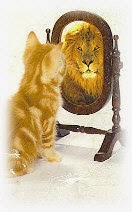

Overcoming Powerlessness

"We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts

comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms -- to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances."-- Victor Frankl

When you feel powerless, you feel afraid to express your needs because you fear (often rightly) that what little you have will be taken from you. You may have learned powerlessness if you were kept in powerless positions repeatedly and/or over long periods of time (possibly during childhood) by those who used external forces (money, physical strength, legal status, and/or military force) to control you. You may have been abused as a child, a partner or spouse, an employee, a soldier, or you may have been the victim of racial or ethnic attacks. Such prolonged abuse can cause you to become afraid to feel even your own needs, i.e., to admit to yourself that you need something. You become immobilized. And in certain critical ways you stop growing, you cease to thrive.

Distinguishing Externally Imposed Powerlessness from Learned Powerlessness

When powerlessness is "learned", it becomes self-perpetuating, even if the external forces are no longer there. An abused child may grow up to feel permanently powerless as an adult, even though his/her parents no longer have physical or economic power over him/her. One may then enter into a situation that repeats childhood experiences (e.g., living with or marrying an abusive partner), and therefore keeping oneself in externally imposed danger. Or one may keep oneself down through self-abuse, compulsive behaviors, and/or depression...because the powerlessness has become internalized.

This is different from the externally imposed powerlessness of racial, class, and gender oppression, which may be enforced through economic, legal, physical, or military, might. The secretary who is being sexually harassed, the single mother who cannot get a promotion due to sex discrimination, the homeless family that cannot afford housing: these are victims that require collective power and direct action to overcome their powerlessness. Collective power may take the form of a union, or a "network" of friends, supporters and professional helpers. Direct action might involve a lawsuit, going to the media, or organizing a strike or protest. Collective power and direct action together make an even more powerful combination.

Even more insidious than this is when--as is often the case--externally imposed powerlessness is combined with learned powerlessness. When this is the case, the above methods are not possible because the person is emotionally incapable of asserting her/his rights.

Overcoming Learned Powerlessness

The first step to overcoming learned powerlessness is to learn to feel entitled to your personal rights. You have the right to live a life free from physical, emotional, sexual, and financial mistreatment. You have the right to be treated with respect, to earn a livable income, to be informed of matters that affect you, and to express yourself freely (without harming others). Most importantly, you have the right to ask for what you need (even though you may be turned down) and to fight for what you need and want (even if you are turned down!). This list of "legitimate entitlements" is easier to read than to experience. Most people who have learned powerlessness barely feel entitled to speak, let alone to speak freely. Often professional therapy is necessary to overcome the ingrained patterns. Never the less, to overcome learned powerlessness, you must gradually, haltingly, but persistently lay claim to each and every human right, one after the other.

Click here to find out about distance learning programs for therapists and here to find out about general training and supervision options.

Labels:

abuse,

assertiveness,

empowerment,

oppression,

power,

self esteem

Friday, February 17, 2012

Improving Body Image

"If we place pornography and the tyranny of slenderness alongside one another we have the two most significant obsessions of our culture, and both of them focused upon a woman's body." -Kim Chernin

Body image involves our perception, imagination, emotions, and physical sensations of and about our bodies. It s not static- but ever changing; sensitive to changes in mood, environment, and physical experience. It is not based on fact. It is psychological in nature, and much more influenced by self-esteem than by actual physical attractiveness as judged by others. It is not inborn, but learned. This learning occurs in the family and among peers, but these only reinforce what is learned and expected culturally.

Body image involves our perception, imagination, emotions, and physical sensations of and about our bodies. It s not static- but ever changing; sensitive to changes in mood, environment, and physical experience. It is not based on fact. It is psychological in nature, and much more influenced by self-esteem than by actual physical attractiveness as judged by others. It is not inborn, but learned. This learning occurs in the family and among peers, but these only reinforce what is learned and expected culturally.In this culture, we women are starving ourselves, starving our children and loved ones, gorging ourselves, gorging our children and loved ones, alternating between starving and gorging, purging, obsessing, and all the while hating, pounding and wanting to remove that which makes us female: our bodies, our curves, our pear-shaped selves.

"Cosmetic surgery is the fastest growing 'medical' specialty.... Throughout the 80s, as women gained power, unprecedented numbers of them sought out and submitted to the knife...." - Naomi Wolf

The work of feminist object relations theorists such as Susie Orbach (author of Fat is a Feminist Issue, and Hunger Strike: Anorexia as a Metaphor for Our Age) and those at The Women's Therapy Centre Institute (authors of Eating Problems: a Feminist Psychoanalytic Treatment Model) has demonstrated a relationship between the development of personal boundaries and body image. Personal boundaries are the physical and emotional borders around us.. A concrete example of a physical boundary is our skin. It distinguishes between that which is inside you and that which is outside you. On a psychological level, a person with strong boundaries might be able to help out well in disasters- feeling concerned for others, but able to keep a clear sense of who they are. Someone with weak boundaries might have sex with inappropriate people, forgetting where they end and where others begin. Such a person way not feel "whole" when alone.

Our psychological boundaries develop early in life, based on how we are held and touched (or not held and touched). A person who is deprived of touch as an infant or young child, for example, may not have the sensory information s/he needs to distinguish between what is inside and what is outside her/himself. As a result, boundaries may be unclear or unformed. This could cause the person to have difficulty getting an accurate sense of his/her body shape and size. This person might also have difficulty eating, because they might have trouble sensing the physical boundaries of hunger and fullness or satiation. On the other extreme, a child who is sexually or physically abused may feel terrible pain and shame or loathing associated to his/her body. Such a person might use food or starvation to continue the physical punishments they grew familiar with in childhood.

Developing a Healthy Body Image

Here are some guidelines (Adapted from BodyLove: Learning to Like Our Looks and Ourselves, Rita Freeman, Ph.D.) that can help you work toward a positive body image:

1. Listen to your body. Eat when you are hungry.

2 .Be realistic about the size you are likely to be based on your genetic and environmental

history..

3. Exercise regularly in an enjoyable way, regardless of size.

4. Expect normal weekly and monthly changes in weight and shape

5. Work towards self acceptance and self forgiveness- be gentle with yourself.

6. Ask for support and encouragement from friends and family when life is stressful.

7. Decide how you wish to spend your energy -- pursuing the "perfect body image" or enjoying

family, friends, school and, most importantly, life.

Think of it as the three A's....

Attention -- Refers to listening for and responding to internal cues (i.e., hunger, satiety,

fatigue).

Appreciation -- Refers to appreciating the pleasures your body can provide.

Acceptance -- Refers to accepting what is -- instead of longing for what is not.

Healthy body weight is the size a person naturally returns to after a long period of both non-compulsive eating* and consistent exercise commensurate with the person' s physical health and condition. We must learn to advocate for ourselves and our children to aspire to a naturally determined size, even though that will often mean confronting misinformed family, friends, and media advertising again and again.

*Simply stated, non-compulsive eating means eating when you are hungry and stopping when you are satisfied. This involves being able to distinguish emotional hunger from physical hunger, and satiation from over fullness. Link to: Compulsive Overeating for more information. Link to: Bibliography to view sources.

Click here to find out about distance learning programs for therapists and here to find out about general training and supervision options.

Bibliography

The Obsession: Reflections on the Tyranny of Slenderness, by Kim Chernin, Harper & Row, 1982.

BodyLove: Learning to Like Our Looks and Ourselves, Rita Freeman, Ph.D., Harper & Row, 1988

200 Ways to Love the Body You Have by Marcia Germaine Hutchinson, EdD , The Crossing Press, 1999

Fat is a Feminist Issue: A Self Help Guide for Compulsive Eaters, by Susie Orbach,

Hunger Strike: Anorexia as a Metaphor for Our Age, by Susie Orbach, Norton Books, 1986

The Beauty Myth, by Naomi Wolf, Doubleday, 1991 to buy click: The Beauty Myth

Eating Problems: a Feminist Psychoanalytic Treatment Model, by The Women's Therapy Centre Institute, Basic Books, 1994

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)